A famous study from 1999 by Lawrence M. Rudner surveyed nearly 21,000 homeschooled students and found that their median test scores were typically in the 70th to 80th percentiles, and that 25% of homeschooled students were enrolled in a grade level that was higher than their public school counterparts.

This study was widely cited by homeschool advocacy groups at the time (and still is—see Facebook, Jenny, Mason, and Thomas for examples), including the Homeschool Legal Defense Association (HSLDA). The HSLDA released the following in their press release about Rudner’s results:

“The largest study ever conducted on home schooling in the United States concludes that in the race to scholastic excellence, typical home school students sprint to the front in the early grades, and generally finish far ahead of students in public or private schools.

“‘Young home school students run one grade level ahead of their counterparts in public and private schools. But by the finish line, home schoolers have pulled away from the pack, typically scoring in the 70th or 80th percentile on the Iowa Test of Basic Skills,’ said Michael Farris, founder and president of the Home School Legal Defense Association (HSLDA)” (HSLDA: Home Schooling Works!)

These are impressive results, and they aren’t an outlier. More recently, a 2009 study from Brian D. Ray of the National Home Education Research Institute included nearly 12,000 homeschooled participants and found that homeschoolers scored a full 34-39 points above their public school peers on an array of standardized tests.

The HSLDA published a full “Progress Report” on Ray’s study, where they suggested that “[t]he biggest news” was that “[h]omeschoolers are still achieving well beyond their public school counterparts—no matter what their family background, socioeconomic level, or style of homeschooling” (HSLDA and Brian Ray).

In citing both of these studies we’re practicing what historians call “corroboration”—we’re checking whether a particular claim is supported or contradicted by other sources. In this case we could say that the Rudner study is “corroborated” by the Ray study.

Historians have a whole litany of questions that they ask about sources as they try to uncover particular historical narratives. A typical litany might look something like this:

1. Source: Who is the author of the source? Is it affiliated with an institution? When was the source created? Where was the source created? Does this information make you skeptical or trusting?

2. Contextualize: Why was the source created? Who was the intended audience? What else was going on at the time? Does this information make you skeptical or trusting? Based on the above, what predictions can you make about the source’s content?

3. Read and infer: What claims are made? Is the evidence convincing What is not said but is implied? What do these implications suggest? Do the language and tone of the source reveal any biases?

4. Corroborate: Do other sources agree or disagree? What explains their differences? Does this information make you skeptical or trusting?

In the history classroom, students are taught to run through these same questions with all of the sources they encounter in order to mimic the rigor of professional historians. Asking these questions about source material helps students think about sources properly, such as looking for the subtleties that come along with different source types, and avoiding the tendency to look at sources in isolation or out of context.

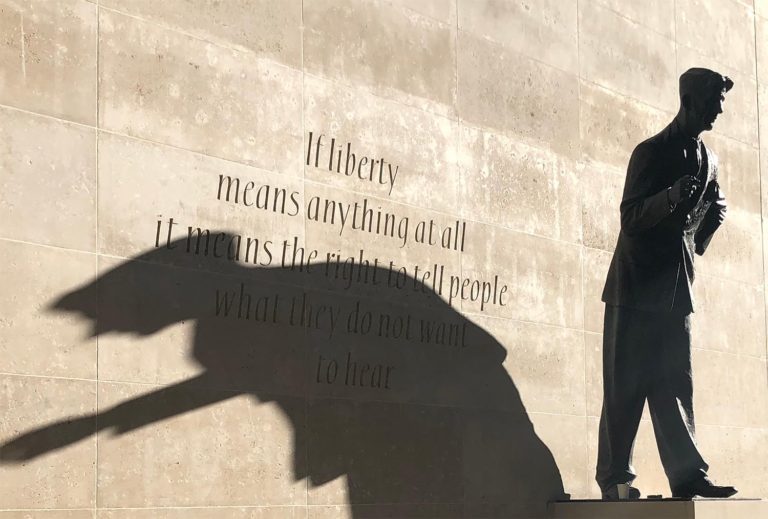

Learning to read all source material (new and old, Facebook posts and medieval scrolls) in this way is a skill that is highly transferrable outside of the history classroom. This is what makes this kind of literacy such a valuable part of a good history curriculum: no matter what a student does after high school they will have to deal with contradictory claims and evidence from every kind of source, from TV and the internet to their own families and peer groups. Knowing how to identify, live with, and/or resolve these tensions and contradictions is an invaluable grown-up skill in any life or career.

If we use these skills to get under the surface of the Rudner study above, it doesn’t take long to come up with some valuable information. I’ll include only the questions that yield the most pertinent results.

Rudner, 1999

Sourcing

Who is the author of the source? Rudner was the director of the ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation with a good reputation as a researcher (McCracken; Rudner)

Is it affiliated with an institution? The study was commissioned by the aforementioned homeschool advocacy group, the HSLDA, and was conceived of and designed by members of the HSLDA, Michael Farris and Earl Hall (Rudner)

Does this information make you skeptical or trusting? This information makes me skeptical because the study was designed and paid for by a group and individuals with a substantial vested interest

Contextualization

Why was the source created? The report’s self-stated goals were to answer the questions, “Are the achievement levels of home school students comparable to those of public school students?” and “How does the home school population differ from the general United States population?” (Rudner; McCracken); reading between the lines leads me to believe that the source was created to generate support for homeschool (Welner, 4)

Who was the intended audience? Based on the media release and press conference the intended audience appears to have been the wider public (HSLDA: Home Schooling Works!)

Does this information make you skeptical or trusting? This information makes me skeptical for reasons similar to the ones listed above

Based on the above, what predictions can you make about the source’s content? The results of this study will probably suggest that homeschool measures up very well to public and private school, perhaps even that a homeschool education is superior to an education from a brick-and-mortar institution

We could go on in this vein and pass Rudner’s study through the last two sets of questions, but perhaps the point is clear: it doesn’t take long to decide how you should approach a particular source, whether you should approach it with a healthy level of skepticism, or with a particular level of justified confidence.

One note of caution: it can be easy at this point to justify dismissing the results of the study as “agenda-driven,” or otherwise unreliable. However, the goal in reading sources carefully is not to justify dismissing opposing arguments before we understand them. Instead, what we’re trying to do is take in new source information in the most informed way possible. Knowing these pro-homeschool results were paid for by a pro-homeschool group doesn’t allow me to dismiss them, since it could be that my prediction is wrong, and that Rudner’s study was conducted with the most careful possible scientific rigor, in which case it could turn out that the HSLDA financing and advocacy did not measurably influence the results.

Instead, knowing these pro-homeschool results were paid for by a pro-homeschool group allows me to read the study in an appropriately careful and skeptical way. That is the habit of mind we want to cultivate in our students. We’re not trying to counter potentially agenda-driven claims with other potentially agenda-driven claims (indeed, much of the opposition to Rudner comes from other pro-homeschool groups and/or researchers), but to evaluate Rudner’s methods, corroborate his results, and contextualize his conclusions in much the same way that Rudner himself tried to do before his results were popularized and misrepresented in the media. In his own abstract Rudner cautions the reader against misapplying his results:

“Because this was not a controlled experiment, the study does not demonstrate that home schooling is superior to public or private schools and the results must be interpreted with caution.”

Instead, the point of this investigation is to use one case study to show how easy it is for students and adults alike to be influenced by superficial claims, bad reporting, incomplete data, and information that hasn’t been properly sourced or otherwise scrutinized before its conclusions are trumpeted out of context. No one wants an incomplete story like this, about homeschool or any other important topic.

And it turns out that there’s no real reason to misrepresent the data on homeschooling anyway. In the years since 1999 and 2009 respectively (perhaps you’d find it interesting to pass the Brian D. Ray study through the series of source questions on your own?), several groups have gone over Rudner’s results with the kind of scrutiny I’ve been suggesting throughout, the kind that professional historians and fact-checkers apply to their own claims and source material (for a sampling see McCracken; Reich; Kaseman; Kunzman; Lubienski; Martin‐Chang; and Murphy). The results suggest that while interpreting Rudner’s conclusions conservatively is probably justified, it is not false to argue that a well-run homeschool is at the very least competitive with a well-run institutional school:

- Rudner’s sample population was not random or representative

- Rudner did not control for background demographics of his participants

- Rudner’s conclusions, while not false, are not generalizable outside of his particular subset of homeschooled students

- After controlling for demographic backgrounds homeschoolers outperformed their peers at one Midwest doctoral institution

- In a comparison of retention and graduation rates no differences were found between homeschooled students and their institutionally educated peers

- “When the homeschooled group was divided into those who were taught from organized lesson plans (structured homeschoolers) and those who were not (unstructured homeschoolers), the data showed that structured homeschooled children achieved higher standardized scores compared with children attending public school. Exploratory analyses also suggest that the unstructured homeschoolers are achieving the lowest standardized scores across the 3 groups.” (This is perhaps unsurprising given their disinterest in standardized objectives and metrics.)

- “One generalization that emerges from many smaller studies on academic achievement is that homeschooling actually does not have that much of an effect on student achievement once family background variables are controlled” (270)

- “A second consistent finding of these studies over the past 30 years is that homeschoolers tend to perform better on verbal tests than they do on mathematics assessments…Given this persistent corroboration across three decades we might conclude, tentatively, that there may be at least a modest homeschooling effect on academic achievement— namely that it tends to improve students’ verbal skills and weaken their math capacities” (271)

- “One obvious reason for the potential finding that homeschooling heightens performance at the extremes of the distribution curve is that it by definition magnifies the role of the parent in a child’s education. A consistent finding in the literature on academic achievement is that parental background matters a lot” (272)

- “Several studies have found that homeschoolers outperform their institutionally schooled peers with similar demographic backgrounds on grade point average [in college]…Studies of other academic variables have found little to no difference between college students who were homeschooled and those who attended traditional schools [such as graduation and retention]…The one category where homeschoolers tended to outperform their peers from other schooling backgrounds was campus leadership—homeschoolers were significantly more involved in leadership positions for longer periods of time” (273)

- “The consistent finding of [college admissions studies] is that homeschooled applicants are accepted at roughly the same rates as their conventionally schooled peers, that admissions staff generally expect homeschoolers to do as well as or better than their conventionally schooled peers in college, and that while colleges and universities welcome homeschooled applicants, most do not go out of their way to provide special services or admissions procedures for them” (273-274)

- “[R]esearch on the lives of homeschooled college students…masks one profound insight that emerges from some of the larger-scale quantitative studies using representative samples: very few homeschoolers take the SAT or ACT or go on to attend selective four-year colleges and universities…Studies of homeschoolers in college are thus not capturing the post-homeschool experiences of most homeschooled children” (274)

- “[From research into education and employment] the clear and unavoidable conclusion of what is probably the most rigorous data set ever created to measure homeschooling’s long-term academic impact is that homeschoolers as a whole do not have great educational and economic success if measured by conventional standards like a college degree and a high-paying job. On the other hand, as several researchers have pointed out, conventional standards might not be what is motivating a large percentage of homeschooling families anyway” (275)

Conclusion

In a follow-up interview to his 1999 study, Rudner actually affirmed some of the above results when he offered his own estimation of the significance of his work:

“I think the real lesson from this report is that parental involvement really affects education. It’s consistent with all the literature,” says Rudner, whose two children attend public schools. “I’m viewing home schooling as the pinnacle of parent involvement” (Brouillette)

Perhaps we would do well to teach our students to learn from the Rudner study and all of its fallout: to practice skepticism and rigorous sourcing; to avoid quick generalizations; to acknowledge limitations in our own understanding and research; to discipline ourselves until we learn to base limited claims on relevant evidence; and to qualify what we do know within its appropriate boundaries.

Students will be happier when a proficient practice of these skills equips them to be more confident, more calm, and more authoritative in all of the different information spaces they will inevitably inhabit.