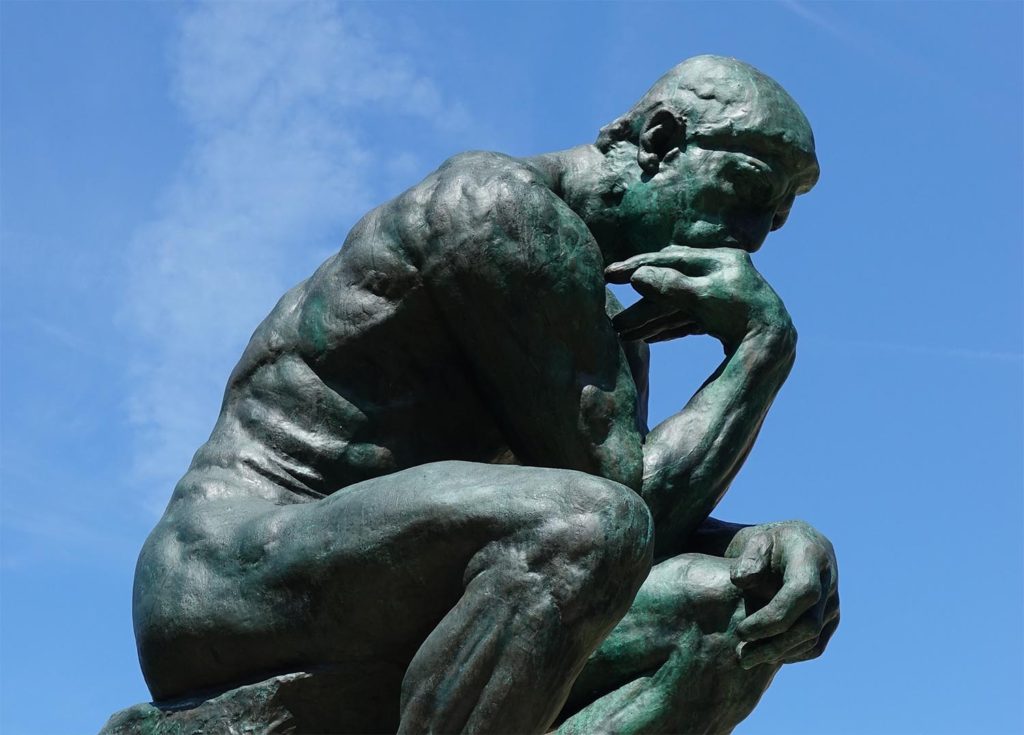

History is a good place to learn how to be skeptical in a good way. The distinction between “good” skepticism and other kinds of skepticism comes out in the following lines from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on “Ancient Skepticism”:

Suspension is a core element of skepticism: the skeptic suspends judgment. However, if this means that the skeptic forms no beliefs whatsoever, then skepticism may be a kind of cognitive suicide.

In other words, there is a difference between (1) refusing to believe that anything is true, (2) accepting all answers as true, and (3) (temporarily) suspending judgment.

Historians are very good at (temporarily) suspending judgment.

Refusing to believe that anything is true

This is something like “radical skepticism.” Properly speaking, radical skepticism is a form of philosophical skepticism which suggests that certainty is never justified. But a version of this extreme kind of skepticism is common. Consider the following positions you’ve probably heard before:

Position 1: The scientific evidence for human-caused climate change is unconvincing.

Position 2: Too many media outlets cherry-pick which scientific conclusions support their environmental agenda.

Position 3: Science is a tool for propping-up politically convenient “facts.”

While all of these positions express some level of doubt or skepticism, the first two make limited claims, while the last one makes an absolute claim. Position 1 is essentially saying: “So far, scientists haven’t convinced me that climate change is caused by humans.”

Whereas Position 3 is saying: “Science can’t be trusted.”

This more generalized and fundamental skepticism is far more radical and far less productive than the narrower statements of doubt in Positions 1 and 2. Duncan Pritchard, Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Irvine, puts it this way:

[O]nce we shift from a localized sceptical doubt to one that is much more general—as when we become sceptical of scientific claims en masse—then it is hard to make sense of how our scepticism is grounded in what we know at all…The worry is that rather than being grounded in something that we can rely upon, as [Position 1] might be, a generalized or wholesale sceptical doubt becomes instead completely free-floating.

We want to learn to avoid these “free-floating” claims. Historical thinking can help us ground our claims in things we can defensibly claim to know.

Accepting all answers as true (or muddying the very idea of “truth”)

Radical skepticism opens the door to different forms of relativism. Peter Graham from UC Riverside defines relativism this way:

Relativism about truth is the view that if you believe that P, then P is true for you, and that is all there is to truth. On the relativist view, there is no such thing as ‘‘objective’’ truth, truth independent of what anyone happens to believe. (398)

This kind of relativism is probably closely related to the popular concept of “post-truth,” chosen as the Oxford Dictionaries’ word of the year in 2016. The Oxford Dictionary defined “post-truth” in this way:

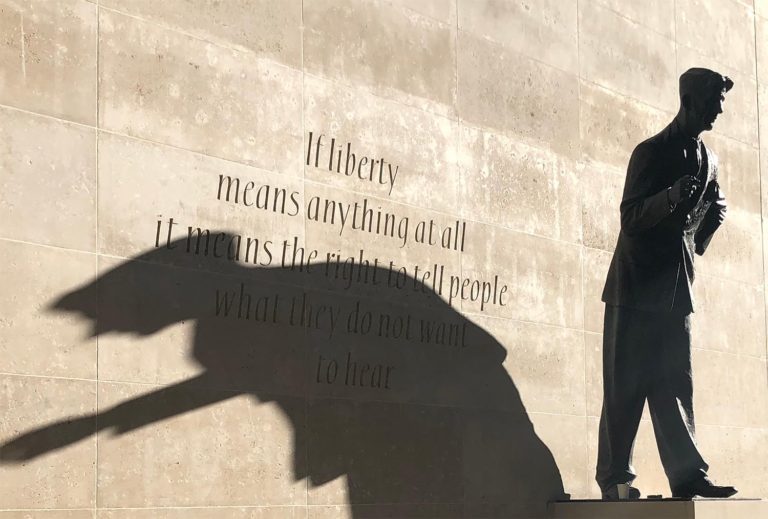

Post-truth is an adjective defined as ‘relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief’.

The German Language Society (GfdS) (who also chose the term “post-factual” as their word of the year in 2016), adds that

Ever greater sections of the population are ready to ignore facts, and even to accept obvious lies willingly. Not the claim to truth, but the expression of the ‘felt truth’ leads to success in the ‘post-factual age’. (Translation from John Keane)

These overlapping ideas of “personal belief” and “felt truth” articulate relativism precisely. That is not to say that we have to agree about everything–scientific scrutiny doesn’t work the same with every subject matter–however, it is to say that many subjects do have right and wrong answers. For example, the following positions can’t both be right at the same time:

Position 1: HIV causes AIDS.

Position 2: HIV does not cause AIDS.

There is a fairly conclusive scientific answer to the relationship between the HIV virus and AIDS. This is not a subject about which one can have a “personal belief” or a “felt truth.” Historical thinking can help us learn how to be skeptical without rejecting the possibility of objectivity.

Temporarily suspending judgment

We’ll call this “healthy skepticism.” Duncan Pritchard explains it this way:

A certain degree of scepticism is often a good thing. Indeed, we talk about the importance of having a ‘healthy scepticism’, where this means not simply accepting whatever one is told. Scepticism in this sense is the antidote to gullibility, and surely no-one wants to be gullible. Some things warrant scepticism after all.

Perhaps this seems too obvious to warrant pointing out–no one wants to be tricked by a slick car salesman, or a flashy commercial for an expensive miracle drug, or a dubious email from the representative of a dead Nigerian king, therefore everyone knows to be skeptical of certain sources.

However, consider a recent report from NewsGuard, an independent agency that specializes in judging the trustworthiness of news sources based on how they score on a rubric of nine published criteria, including transparency regarding ownership, transparency regarding political bias, how frequently they publish inaccurate claims, and how frequently they rely on clickbait for engagement. According to NewsGuard, unreliable websites enjoyed a 305% increase in engagement from 2019 to 2020, as opposed to a 69% increase in engagement with reliable websites over the same period.

At the very least this trend warrants attention. In the worst case, it could suggest that we are becoming more gullible, not less; more susceptible to emotional reasoning, not less; more partisan and subject to tribal thinking, not less; more prone to confirmation bias, not less; more blind to our own biases and illogical thinking, not less. If any of these are in fact true, they warrant a discussion about possible solutions.

Conclusion

Learning to think like a historian–learning to practice “healthy skepticism”–is not a magical antidote or a guaranteed solution to the problems of radical skepticism and relativism, but it is a start, and it can provide a level of personal security against an information space that is not likely to fix itself anytime soon. To find out more about how to think like a historian, consider some of the suggested resources below, as well as the document lessons at the end of every unit in each Nomadic course (nomadicprofessor.com).

As always, this is my two cents—but I’m a champion for honest conversation and civil dialogue, so tell me what you think in the comments below!

Bibliography

Graham, Peter J. “The Relativist Response to Radical Skepticism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Skepticism, edited by John Greco, 392–414. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2011.

Keane, John. “Post-Truth Politics and Why the Antidote Isn’t Simply ‘Fact-Checking’ and Truth.” The Conversation, August 20, 2020. https://theconversation.com/post-truth-politics-and-why-the-antidote-isnt-simply-fact-checking-and-truth-87364.

“Oxford Word of the Year 2016.” Accessed December 28, 2020. https://languages.oup.com/word-of-the-year/2016/.

Pritchard, Duncan. Scepticism: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions). OUP Oxford. Kindle Edition.

“Special Report: 2020 Engagement Analysis.” NewsGuard, December 21, 2020. https://www.newsguardtech.com/special-report-2020-engagement-analysis/.

Spiegel, Der. “‘Postfaktisch’ Zum Wort Des Jahres 2016 Gekürt – DER SPIEGEL – Kultur.” DER SPIEGEL. DER SPIEGEL, December 9, 2016. https://www.spiegel.de/kultur/gesellschaft/wort-des-jahres-2016-postfaktisch-gekuert-a-1125124.html. (English translation from Google Chrome.)

Vogt, Katja. “Ancient Skepticism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University, July 20, 2018. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/skepticism-ancient/.

Suggested Resources

ground.news – a news aggregator that judges the political bias of news outlets and brings all the coverage of a given story together into one place to help you quickly discern media bias from neutral coverage

newsguardtech.com – offers trust ratings and “nutrition facts” for the Internet’s most visited sites

sheg.stanford.edu – offers free history lessons that help teach the skills of healthy skepticism

cor.stanford.edu – offers free internet literacy lessons that help teach the skills of healthy skepticism

CTRL-F – a YouTube channel with a similar mission to cor.stanford.edu