If you’ve been to one of our in-person or online sessions on teaching history, you may have heard us talk about the value of knowing the past for understanding and making informed judgments about the present. While this prerequisite is not new, and our articulation of it is not original, it is a prerequisite that is worth emphasizing—and doing so often.

Saying that knowing the past can help you make judgments about the present is slightly different than repeating the old cliché that “history repeats itself.” While there are certainly patterns in human behavior, it’s not quite true to say that history “repeats itself,” when every new moment happens in a changed context. It can be easy to miss out on rich and useful nuances from one moment to the next if we’re too quick to reduce periods of time to copies of each other.

When we argue that knowing the past is an important part of being an informed judge of the present, we’re also speaking to the common experiences of confusion and susceptibility. It is confusing to read the headlines if we don’t know where they’re coming from. The recent examples are too many and obvious to need a full recounting—Ukraine and Russia, China and the Uighurs, the fallout from the George Floyd murder, COVID-19, and so on.

Yet confusion can be a natural and even positive response to the headlines. If you’re comfortable acknowledging that you’re confused or uncertain, you are epistemically humble, or willing to admit what you don’t know. This is a capacity that should probably be cultivated, not hidden shamefully away because there is social pressure to have immediate moral convictions about everything that happens.

But we don’t always have to be confused, and it can be empowering to read a headline and know some context that helps you make sense of it. Having this context can make you less susceptible to misguided ideas and movements; can help you and your students avoid tribal thinking, emotional reasoning, decisions based in ignorance, and any number of other pitfalls.

Ignorance is perhaps an under-emphasized, and even dangerous, failing, but it is one over which individuals have an immense amount of control. In a recent book, The War on the West, Douglas Murray highlighted the problem of ignorance:

The only thing modern Western populations are more ignorant about than their own history is the history of other peoples outside the West. Yet such knowledge is surely a prerequisite to being able to arrive at any moral judgments. A poll of young British people carried out by Survation in 2016 found that 50 percent had never heard of Lenin, while 70 percent had no idea who Mao was. Among sixteen- to twenty-four-year-olds, who had all grown up after the fall of the Berlin Wall, 41 percent had positive feelings about socialism, while just 28 percent felt the same sentiments toward capitalism. One possible reason for this is that 68 percent said they had never learned anything in school about the Russian Revolution.

Equal if not greater ignorance can be found in America. A poll carried out in 2020 found that almost two-thirds of Americans between the ages of eighteen and thirty-nine had no idea that 6 million Jews were killed in the Holocaust. According to the study, almost half of Americans in their twenties and thirties could not name a single concentration camp or ghetto established by the Nazis during World War II. About one in eight young Americans (12 percent) said that they had not heard of the Holocaust or didn’t think that they had heard of it…

It is worth keeping figures such as this in mind as we see the next manifestation of the war on the West. The assault on Western history.

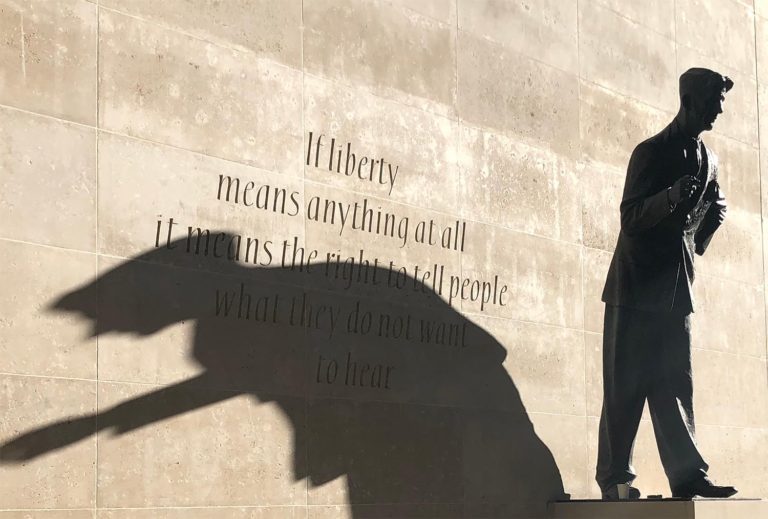

When people claim that populations are ignorant of the history of the West, they forget that most people are ignorant about almost everything. When critics claim that there is something sinister about their particular area of interest being too little known about, they forget that majorities of young people across the West have no serious knowledge even of one of the greatest crimes in history. So this is a delicate as well as a sinister moment. Because when you are speaking into a great vacuum of ignorance, people with malign intent can run an awfully long way awfully fast. They can tell their listeners things that they will simply believe and tell them what they should not question…(emphasis added)

Murray, Douglas. The War on the West (pp. 76-82). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

It is often said that disciplines like history have little practical value; historians know a bunch of stuff, but can they do anything? Why do we need to study history when we have Google in our pockets?

There are many ways to answer this question, but, as Murray suggests, perhaps none is more important than building in some critical distance between you and all of the various forces with their own stories tell, stories that you can’t reliably judge without your own clear picture of the past.