I was once in a faculty meeting to decide on a coherent school smartphone policy. We were in the drama room on the stage of a kind of amphitheater, sixty of us sitting across from each other in a large circle. You could tell the teachers apart by the way they dressed and who they sat with—the buttoned-up science guys, the loungy PE teachers, the coffee-from-a-jar humanities group.

The conversation wasn’t easy because the facilitator wanted to hear from lots of people, and lots of people didn’t care, and others cared a lot. I was one of a small handful of teachers in favor of a smartphone ban, but I hadn’t prepared for the meeting, and wasn’t feeling particularly plugged into the conversation.

A wiry science teacher raised his hand and made something like the following point:

Students are going to have to know how to use technology responsibly in college and adult life, so they might as well learn how to do that in high school. We shouldn’t take that valuable learning experience from them.

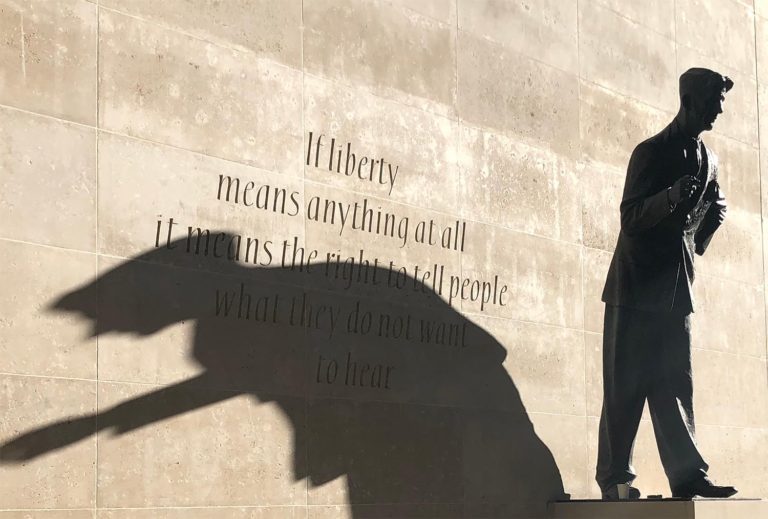

I raised my hand and made something like the following point:

The research shows that students don’t learn as much when they’re distracted.

The silence that followed my comment assured me that I had indeed failed to articulate my point in a resounding way, but nothing else was coming to me. The meeting ended, and not much changed.

It’s been over five years now, and I still think back on the meeting, and the importance of thinking clearly about smartphones and adolescents. Here are a few questions worth considering:

Is smartphone-style distraction a “learning experience,” or are we normalizing inattentiveness and multi-tasking?

We impose age-related regulations on alcohol, drugs, sex, guns, credit cards, and other things—is there a parallel to be drawn with smartphones?

Can difficult schoolwork compete with the ease, speed, boundarylessness, and entertainment of the smartphone?