In college I had a history teacher who didn’t teach us history. Instead he gave us two texts—A Patriot’s History by Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen, and A People’s History by Howard Zinn—and assigned us to read excerpts on overlapping time periods from both. That was our education in the “content” side of American history, or the “who, what, where, when, and how” of the story.

I liked this approach—the classroom time was discussion heavy, and for homework we got to break down two very different texts and analyze their competing stories. It was exciting to read both texts like I had insider information: neither text knew I was consulting its nemesis to help me judge its claims.

Both texts reveal their sympathies right in their titles: A Patriot’s History of the United States: From Columbus’s Great Discovery to the War on Terror; and A People’s History of the United States: 1492-Present—and then further in their opening pages:

Patriot’s: [W]e remain convinced that if the story of America’s past is told fairly, the result cannot be anything but a deepened patriotism, a sense of awe at the obstacles overcome, the passion invested, the blood and tears spilled, and the nation that was built.

People’s: My viewpoint, in telling the history of the United States, is…[that the] history of any country, presented as the history of a family, conceals fierce conflicts of interest …between conquerors and conquered, masters and slaves, capitalists and workers, dominators and dominated in race and sex. And in such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people, as Albert Camus suggested, not to be on the side of the executioners.

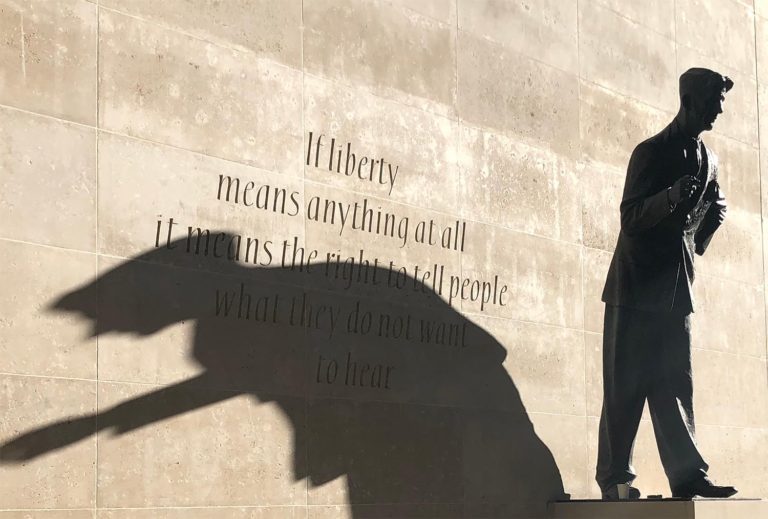

The most obvious problem with these texts is that they filter so much nuanced history through such narrow filters—one is either a “patriot” or an “executioner.” Those are extreme options. It should be possible to write a more nuanced story that articulates the humanity of both the “winners” and the “losers.”

But there is another problem with the way we used these texts in class. My Professor told us why he chose to teach us the “what happened” part of history with excerpts from two very selective histories: he said it was because we all have Google, so we can all look up the “facts” anytime we want. What we didn’t have were skills for discerning between different versions of the facts when we had them, and that’s what he was trying to help us build—a useful set of skills for good historical judgment.

This approach resonated with me at the time. I was a philosophy student and liked asking questions and getting abstract. I began to dismiss the importance of “knowing stuff” in favor of being able to read carefully and know what questions to ask about any given claim, whether I had all of the right context or not. I didn’t have to know the facts if I knew how to find holes in the argument.

I’ve since discovered that both the facts and the skills are necessary.

I’ve been thinking about this balance of facts and skills because my stepdad was over recently, endlessly watching Fox News’s coverage of the American departure from Afghanistan. I needled him about consuming a healthier information diet, with a broader range of sources that do more than trivialize the other side and affirm what he already thinks. He asked me what I thought of the war, and it was easy to dodge his questions when he framed them by asking which “side” I was on, conservative, liberal, Republican, Democrat, independent, etc. But when he dropped that framing and asked me whether we should have gone to Afghanistan in the first place, and whether we should have gotten out differently, I didn’t have the content knowledge I needed to give him a really informed answer.

This is one place where the argument that Google can replace “knowing stuff” falls short: how can Google quickly give me the facts I need to judge American involvement in Afghanistan against another conflict in a different time and place, say Vietnam, or 19th-century colonialism? How can Google quickly summarize decades of military and diplomatic events in a complicated foreign environment with its own culture, politics, and history? How can Google quickly help me frame a new event with the right political, economic, or historical lens?

The short answer is that Google can’t do these things, not in the way we imagine. By itself it is not a replacement for having facts at our disposal that can make help us make sense of the world in real time. We need those facts at our disposal if want to avoid being orientation-less in the face of every new and potentially confusing development in the world. While it doesn’t make sense to become a human encyclopedia without any skills for using or interpreting all of that information, it also doesn’t make sense to become a logic wizard with no facts at your disposal.

If our history classrooms could do these two things—(1) offer a rich and nuanced content, and (2) provide training in how to identify and judge evidence, conclusions, and biases—they could make themselves an integral part of raising and educating informed and careful people. These kinds of people will no doubt be a good influence in our politically and culturally polarized climate.

This is a lofty but worthy goal for a school subject that is increasingly sidelined or taught without nuance, or even overlooked altogether in favor of programs with more “practical” outcomes. I can’t think of anything more practical than a student with the knowledge and skills necessary to assimilate new information with self-assurance, clarity, and competence.

As always, this is my two cents—but I’m a champion for honest conversation and civil dialogue, so tell me what you think in the comments below!