*NB: Access the student guide using the link after the article.

In George Orwell’s 1984, the hero, Winston Smith, gets tortured and indoctrinated by a member of the Inner Party. Here’s an excerpt from that scene (name of Inner Party member replaced with “IPM” to avoid spoilers!):

“There is a party slogan dealing with the control of the past,” IPM said. “Repeat it, if you please.”

“‘Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past,’” repeated Winston obediently.

‘“Who controls the present controls the past,’” said IPM, nodding with slow approval. “Is it your opinion, Winston, that the past has real existence?”

Again the feeling of helplessness descended upon Winston. His eyes flitted towards the dial. He not only did not know whether “yes” or “no” was the answer that would save him from pain; he did not even know which answer he believed to be the true one. (284)

At this point in the story the reader knows Winston well, and can feel his pain and confusion, and can even feel complicit in his wavering commitments. The reader also knows IPM and the infuriating dogma that props up IPM’s tremendous arrogance. The relationships and themes brought out in this scene hit home.

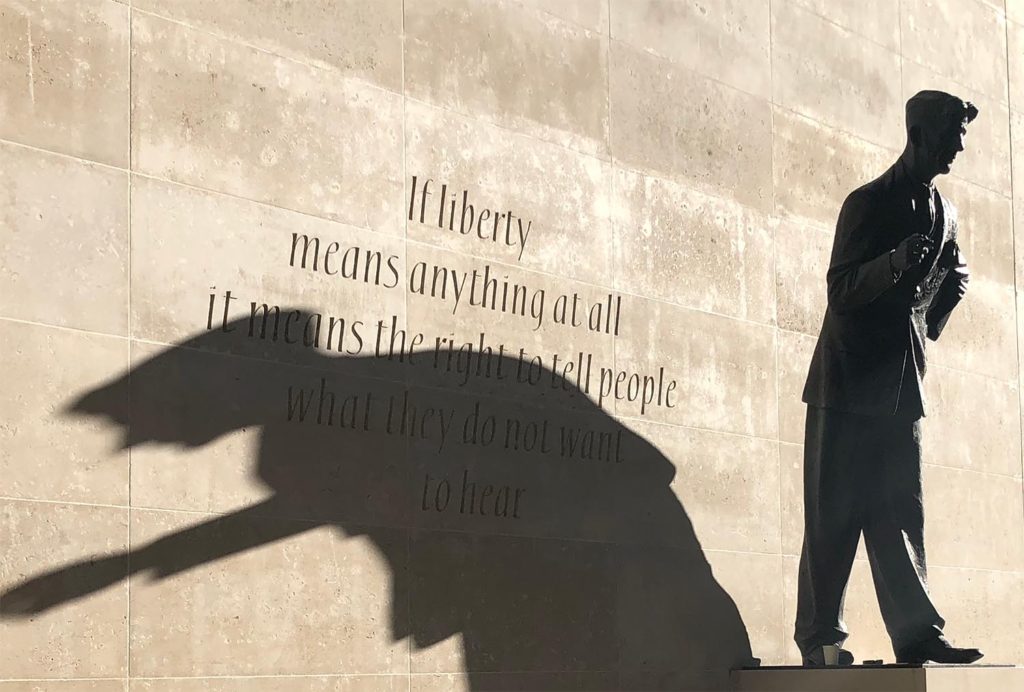

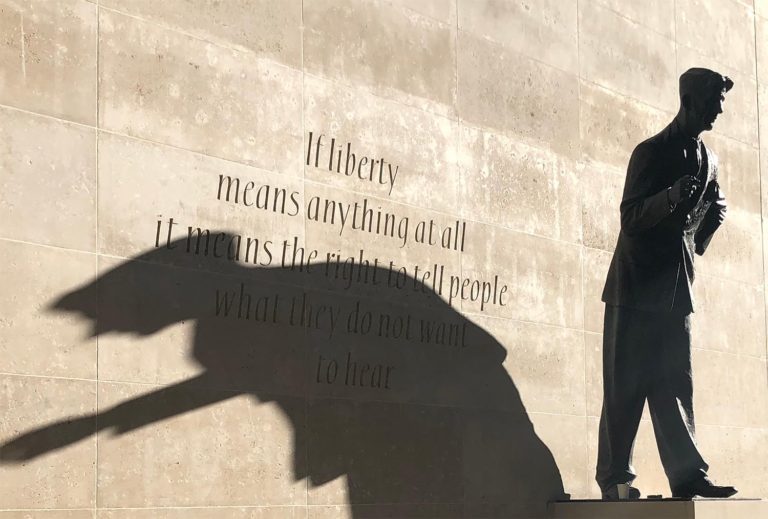

But the point here is only partly about Orwell’s big arguments on censorship, ideology, and control. Before we can come back to those arguments, we need to address the important question IPM raises, the one that elicits so much confusion from Winston:

- Does the past have real existence?

Without any of the same sinister intent, parents and students actually ask related questions all the time:

- Do you teach history with a neutral point of view?

- What worldview do you teach from?

- Is your course political?

That is, parents and students implicitly acknowledge that people interpret the past differently, and they want to know if the version of the past we’re teaching aligns with their worldview, has ulterior motives, tries to be fair and balanced, and so on. Their questions are related to IPM’s question because both are implicitly based on assumptions about a “right” and “wrong” version of the story, or an “objective” and a “subjective” version of the story.

These questions probably revolve around these two areas of concern:

- the point of view and biases of the historian, and

- the motivations and objectives of the historian.

Let’s look at these areas of concern in order to answer IPM’s question, as well as questions about the way the Nomadic Professor approaches the past.

Point of view and bias

Point of view (hereafter POV) and bias are inevitable; the only real question is whether someone allows their POV and biases to be checked, modified, or corrected by new evidence.

The German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer talked about “point of view” in this way (emphasis added):

The history of ideas shows that not until the Enlightenment does the concept of prejudice [or “point of view” or “tradition”] acquire the negative connotation familiar today. Actually “prejudice” means a judgment that is rendered before all the elements that determine a situation have been finally examined… For someone involved in a legal dispute, this kind of judgment against him affects his chances adversely… But this negative sense is only derivative. The negative consequence depends…on the value of the provisional decision as a prejudgment, like that of any precedent.

Thus “prejudice” certainly does not necessarily mean a false judgment, but part of the idea is that it can have either a positive or a negative value… There are such things as [legitimate prejudices]. (273)

The first thing to be said about this quote is that Gadamer is talking about POV somewhat differently than many of us will be used to thinking about it. In this excerpt, a person’s POV is more than “the argument they find convincing,” or “their opinion.”

In fact, POV includes everything about a person, such as their age, gender, nationality, language, family, culture, religion, history, interests, prior experience, occupation, criminal record, health, height, weight, education, and so on. All of these things make up the background within which their opinions and judgments are formed. Talking about POV is the same as talking about the way a person sees the world, and the experiences and realities that have formed and shaped that view.

Talking about POV in this way goes far beyond talking about POV as mere “opinion.”

Consider Gadamer’s example of a legal dispute: doesn’t this fuller understanding of POV help explain why attorneys have to agree on which jurors get to serve on any given jury—because some jurors have a POV (i.e., a background that might include language, criminal record, financial ties, gender, education, ethnicity, and so on) that could keep them from being fair and impartial?

With this in mind, we can understand Gadamer a little better: in a nutshell, Gadamer is arguing that a person cannot escape their POV, and that, in fact, their POV is the only thing that gives them a frame of reference within which they can judge new information. The confrontation between a person’s previous judgments and new information is the critical point, where two things can happen:

- the new information can compel them to modify their previous judgments, or

- the new information can fail to compel them to modify their previous judgments.

Everyone should always be open to (1). The problem with dogmatism and ideology is that they almost always result in (2). But a person’s POV does not have to be ideological or dogmatic; it can be rigorous and committed, but simultaneously open to revision.

These suggestions about POV explain why it always takes a little elaboration when we get asked whether our courses are “neutral.” The answer is always “yes” and “no.”

- Do we avoid ideology and dogma? Yes.

- Is it possible to write and speak from a POV-less POV, or a completely neutral place? No.

We can only write the narrative we find convincing based on our research and experience. There is no “view from nowhere.” We work hard to address this reality by being forthright throughout our courses: we constantly remind students that they are reading an argument, not an authoritative, voiceless textbook, posing as The Final Answer. Further, we actively and rigorously train them in how to identify evidence and challenge conclusions, even our own evidence and conclusions, while avoiding the unnecessary headache of pretending that “all answers are equally valid.”

To sum, while the past has no “real existence” in the sense of an objective or authoritative account of how to interpret it, it does have a “real existence” in the sense that a person is not free to make it mean whatever they want it to mean. Our POV and biases are just the starting point for developing a compelling argument about what the past means; they are not necessarily threats that indicate bad scholarship or ulterior motives.

*NB: For another take on bias and reliability, see Common Error #2.

Motivation and objectives:

Having an inescapable POV that informs your argument and conclusions is very different from pushing ideology as if it is history (these two gems—1 and 2—come up in American History Part 2: The Noise of Democracy, document lesson 2.5; notice the extent to which they use the same history to support opposite policy objectives).

As concerned parents know, the goal of pushing ideology is to convert, indoctrinate, or otherwise convince students that one narrative is the most justified, righteous, and worthy of support.

This is a dishonest approach because it starts with a conclusion (often something flagrantly partisan), then looks for historical evidence to support that conclusion. It reverses the time-tested process of open-ended inquiry by starting with the answer it wants to find, then selecting the sources that support that answer, instead of starting with all of the sources, and being open to the answers they suggest.

This is not history, this is activism. Activism is “campaigning for social and political causes,” and it goes without saying that it is very difficult to campaign for a cause and be balanced in your investigation of the history of that cause at the same time.

This is why activists are often guilty of doing bad history, or history that is selective, ideological, combative, cartoonish, and otherwise narrow or dogmatic. This kind of history can turn real, muddy, and complicated people and stories into unreal caricatures that make difficult questions seem laughably obvious. When an important historical question seems like it has a laughably obvious answer, that should raise a red flag in your mind, and alert you to the need to continue reading in other sources in order to get a better sense of all the possible nuance.

When history is made to seem like an obvious story of good versus evil, it is more like a comic book than history. “Comic book history” is history that is told as if there are obvious and uncomplicated heroes and villains, just like in comic books (the ones where the story is not well told): Batman is righteous, the Joker is evil; Captain America is righteous, Red Skull is evil; the X-Men are righteous, Apocalypse is evil; and so on. In this world things are simple, people are unambiguous, nobody holds competing ideas in unresolved tension, nobody changes their mind, nobody exists in a foreign historical context, etc. etc. etc.

This kind of history should not sit well with anyone reading this post, because it can’t possibly be justified based on experience. In a given day, week, month, or year, most of us probably encounter very few people who are unambiguous, uncomplicated, and perfectly one thing or another (if we encounter any at all—I doubt that we do). We should assume the same is true about people in the past, too.

So if the goal of Nomadic History courses is not indoctrination, political partisanship, or comic book easiness, what is it?

As we see it, a good history class should do two things:

- develop a broad and balanced historical knowledge base, and

- develop historical literacy, or the advanced skills for reading, writing, and thinking that professional historians have to learn in order to make sense of the past.

That’s it. That’s what a good history class does. If a history class goes beyond these two things, there’s a good chance it’s not doing history anymore.

The 1984 excerpt quoted above goes on:

IPM smiled faintly. “You are no metaphysician, Winston,” IPM said. “Until this moment you had never considered what is meant by existence. I will put it more precisely. Does the past exist, concretely, in space? Is there somewhere or other a place, a world of solid objects, where the past is still happening?”

“No.”

“Then where does the past exist, if at all?”

“In records. It is written down.”

“In records. And—?”

“In the mind. In human memories.”

“In memory. Very well, then. We, the Party, control all records and we control all memories. Then we control the past, do we not?”

“But how can you stop people remembering things?” cried Winston, again momentarily forgetting the dial. “It is involuntary. It is outside oneself. How can you control memory? You have not controlled mine!”

“On the contrary,” IPM said, “you have not controlled it. That is what has brought you here… You believe that reality is something objective, external, existing in its own right. You also believe that the nature of reality is self-evident. When you delude yourself into thinking that you see something, you assume that everyone else sees the same thing as you. But I tell you Winston, that reality is not external. Reality exists in the human mind, and nowhere else…” (284-285)

This last line is among the most sinister in all of 1984: “Reality exists in the human mind, and nowhere else.”

IPM is dictating a radical skepticism and a supreme submission to tyranny. And while we (the world circa 2021) have clearly not yet fully arrived in IPM’s world, it is actually not hard to find examples where this belief about the primacy of a “personal reality” has won out in popular culture: talk of “post-truth,” and all of the technologies that (ironically) facilitate division, isolation, and resentment, instead of connectedness, unity, and dialogue; that make it easier for us to be deceived into thinking that the past means what we want it to mean, that it magically and unambiguously supports current political trends, that it is a black and white story about good versus evil culminating in our righteousness, that it is a damning record of oppression and failed attempts at progress, etc. etc. etc.

While Orwell’s vision and argument about the dangers of and trends toward a totalitarian state are well-established, he may also be suggesting a more subtle kind of totalitarianism, one that doesn’t get talked about as much: the total control of our collective past by individuals, among them activist, ideological, and comic book historians unwittingly living out IPM’s most sinister message to Winston: “[R]eality is not external. Reality exists in the human mind, and nowhere else.”

So whose “side” is the Nomadic Professor on? Everyone’s and no one’s. Partisanship is not really compatible with doing good history.

As always, this is my two cents—but I’m a champion for honest conversation and civil dialogue, so tell me what you think in the comments below!

Download the student guide here.